Sports

Meet Gypsy Joe Harris, the Blind Boxer Who Won 24 Pro Fights Before the Truth Came Out

It almost sounds too bizarre to be true, but Gypsy Joe Harris was pretty close to becoming a professional boxing legend. Some might say he was a legend. He may never have reached the level of Mike Tyson or Sugar Ray Leonard, but Gypsy Joe went 24-1 as a pro before the truth caught up to him and cost him his boxing career.

Gypsy Joe Harris began boxing at age 10

Gypsy Joe Harris was born Dec. 1, 1945, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He began boxing somewhat by accident at the age of 10 when he knocked an ice cream cone out of the hand of a man who was walking down the street. The man chased Harris into a guy, run by the Police Athletic League.

‘‘I escaped into a gym, and from then on it was my life,” Harris said in a 1989 story in the Chicago Tribune. “A guy had an ice cream cone in his hand, and I knocked it off. I might never have become a fighter. That’s really something when you think about it.” What’s more impressive is what happened after that.

One year later, on Halloween, Harris got into a fight and a kid threw a brick at him, hitting him and blinding him in the right eye. Harris continued to box with the handicap, winning a pair of Golden Gloves titles as an amateur.

Gypsy Joe made his pro debut in 1965

Gypsy Joe Harris made his pro debut in 1965 and defeated Freddie Walker. The win over Walker began a pro career that saw him win his first 24 bouts. In 1967, Harris was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated as his career began to take off.

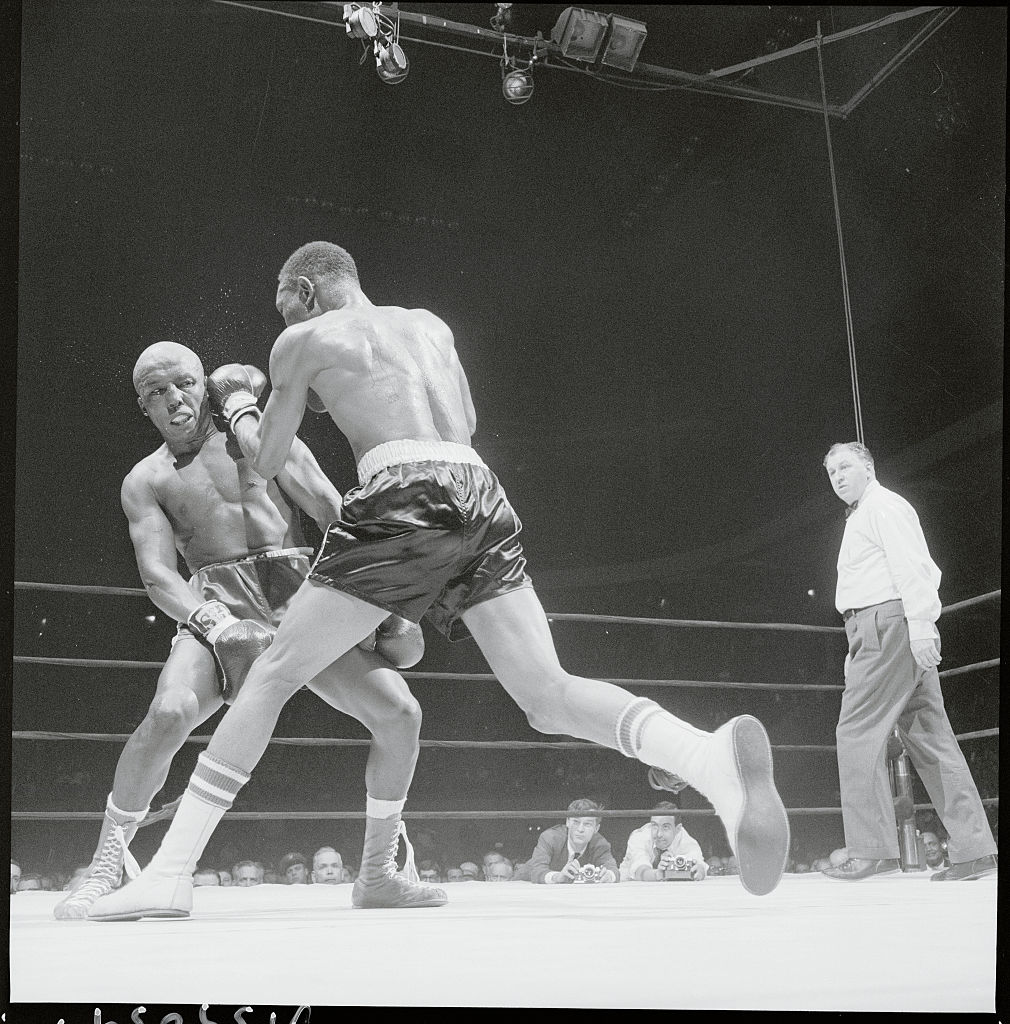

The Sports Illustrated article described the fighting style of the 5-foot-5 Harris as being all over the place. He had a style similar to that of Sugar Ray Robinson. Mark Kram, the author, wrote, “His punches pile out from all angles, and they are thrown from any position. He is a machine gun and a jester, with a Chaplinesque walk and the brass of a pickpocket. Frequently, with his arms dangling by his sides, he gives you his chin to hit, and sometimes, in a corner, he will hold the rope with one hand and keep cracking you with the other.”

Little did Kram or anyone else know at the time that Gypsy Joe was fighting with one eye. He had to line up his opponent a certain way in order to see him. Even Gypsy Joe himself was quoted as saying, “I don’t make plans. I just fight. The guys I fight don’t know what I’m gonna do next, because I don’t know what I’m doing.”

Harris’ career came to an end when the truth was told

Gypsy Joe Harris’ lone loss came on Aug. 6, 1968, when he lost a decision to Emile Griffith. The loss was the first of Harris’ career and the fight would also be his last.

During a prefight physical in October of 1968, one of the doctors noticed an inflammation around Harris’ eye and ordered a more detailed check. It was there that Dr. Harold G. Scheie noticed Harris was blind in the eye and Gypsy Joe’s boxing license was revoked, ending a promising career.

Harris said his camp knew about the handicap for the duration of his pro career and didn’t blame anyone for letting him fight. ”My camp knew I was blind,” Harris said in the Chicago Tribune article. ”If you got a boxer, and he’s blind in one eye, and he goes into the ring and he be holding his own, and he can win and make you money, wouldn’t you let him fight? Wouldn’t you? I don’t blame them. How could I blame them? I was only doing what I wanted to do.”

Gypsy Joe’s life after boxing

After his career abruptly ended, Gypsy Joe worked various jobs but was never as passionate about any of them as he was with his boxing career. He struggled with drugs and alcohol and suffered four heart attacks, the final one killing him on March 6, 1990 at age 44.

Harris died at Temple University Hospital, where he had been a patient for nearly a month. His sister, Daaiyah Waheed, attributed the death to heart failure.

Although the date of his death will go down as March 6, 1990, Harris’ lust for life died when the truth about him having vision in just one eye was found out in 1968. He was a boxer, a fighter, and it was all abruptly taken away from him. ”When they stopped me, I was broken,” he said in the Chicago Tribune piece a year before his death. ”It was like taking a brick and throwing it at a mirror. To me, it was the deepest hurt. It was like a piece of me had died. They killed me.”