Sports

Olympic Star Flo Hyman’s Tragic Death Saved Lives

Flo Hyman’s greatest contribution to sports had nothing to do with leading the U.S. women’s volleyball team to a silver medal at the 1984 Olympics as the best hitter in the world. Rather, what she did most of all was help save the lives of others through her own tragic death at the age of 31.

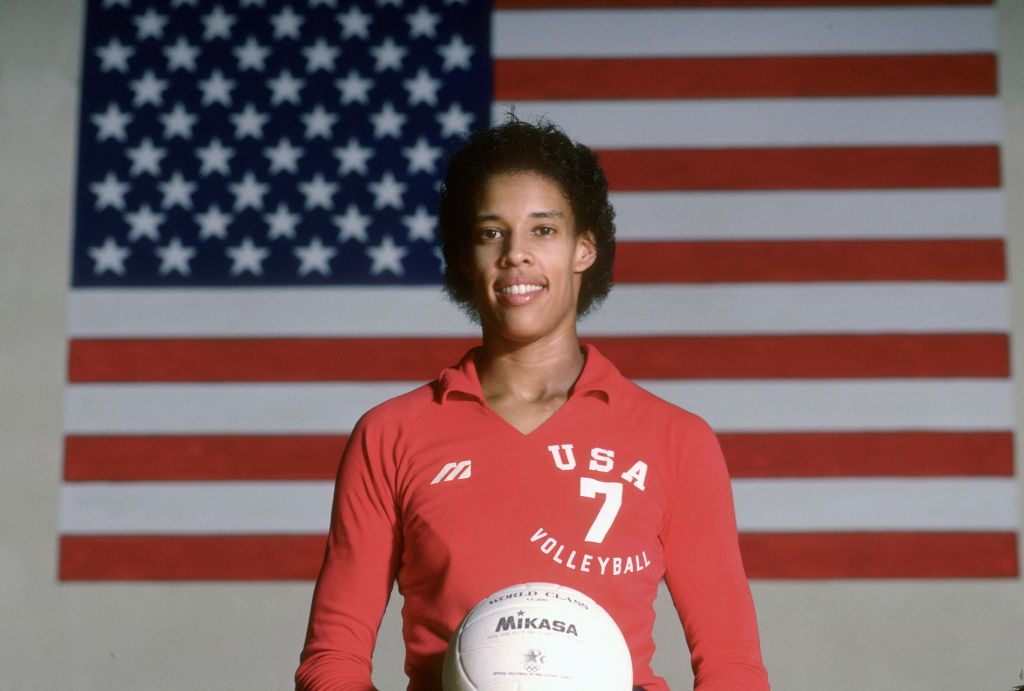

Flo Hyman was an Olympic star in 1984

A Sports Illustrated feature in 1999 rated Flo Hyman as the 69th greatest female athlete of the century. Had she played a more visible sport and been able to compete perhaps once more in the Olympics, there’s no telling how much higher she could have ranked.

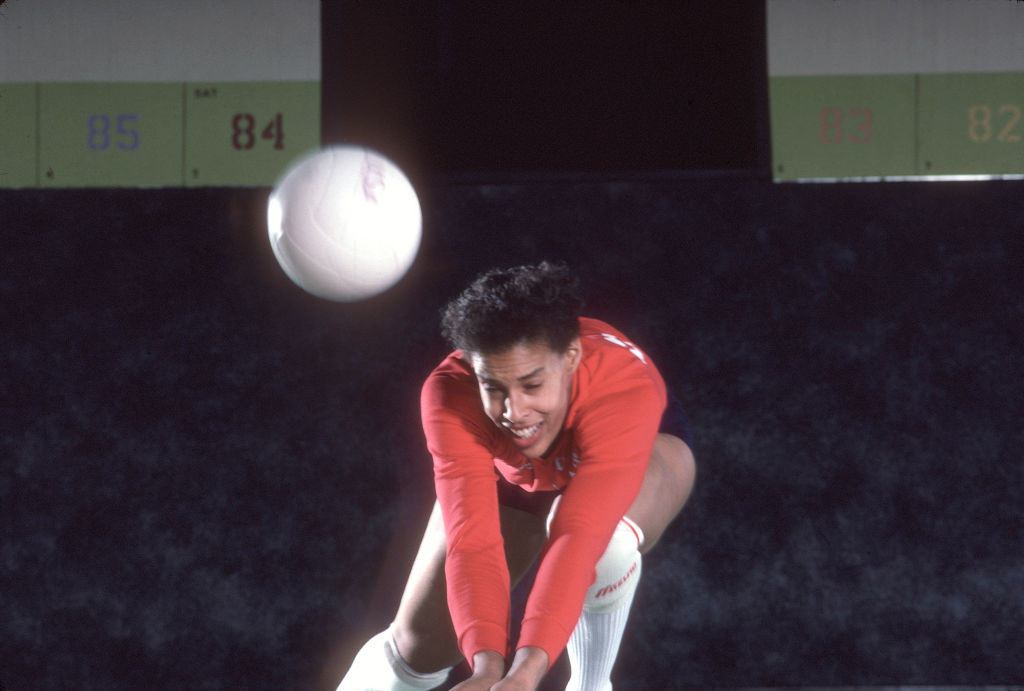

Hyman was a 6-foot-5 hitter whose power and accuracy at the net helped lift the national team from an also-ran to a world championship contender. The squad failed to qualify for the 1976 Montreal Olympics and had to sit out 1980 due to the U.S.-led boycott. Hyman then led the team to bronze medals at the 1981 World Cup, where she was selected the best hitter, and the 1982 World Championships.

At Los Angeles in 1984, she led her team past China in a pool-play match before the United States fell short in the rematch for the gold medal.

Along the way in her career, Hyman was a three-time college All-American, the AIAW National Player of the Year in 1976, and a frequent all-tournament team selection.

“People chanted her name, ‘Hy-man! Hy-man!’ in gyms all over the world,” longtime teammate Laurie Flachmeier told the Los Angeles Times. “She was the first one kids wanted to reach out and touch when we walked through a crowd.”

Flo Hyman’s tragic death in Japan shocked the sport

RELATED: Sugar Ray Leonard Lied About His Age so He Could Try Out for the Olympics

As is still the case, there was more money to be made overseas than at home for elite American volleyball players. Hyman stood out both for her long, athletic body and her skill, making her one of the top attractions of a league in Japan where she was playing what was expected to be her final season.

After being subbed out during a match on Jan. 24, 1986, Hyman took a seat on the bench and was cheering on teammates when she slumped over before a sold-out crowd. She was carried out on a stretcher and had no pulse when the ambulance reached a nearby hospital. She was pronounced dead shortly afterward.

Hyman had experienced fainting spells previously, but doctors could find nothing wrong with her. The initial assumption was that her death might be tied to cardiac arrest or heart disease, but that proved incorrect.

Instead, and autopsy pointed to Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder that as many as 150,000 Americans may have – most without knowing it. The most serious complications involve aortic aneurysms. In Hyman’s case, a weak spot in her aorta immediately above the heart gave way.

A death results in greater emphasis on physical exams

As an elite athlete, Flo Hyman underwent frequent physicals and exams during her career. Her fainting spells resulted in more extensive cardiovascular testing, but Marfan syndrome (MFS) was considered so rare that she was never tested for it.

In retrospect, however, Hyman was probably a classic candidate for further testing. Her tall, thin frame and elongated fingers should have been red flags. Those with Marfan syndrome are also prone to scoliosis and have unusually flexible joints.

There is no cure for MFS. Some people go through their lives not knowing they have it, while many others experience normal life expectancy with the help of beta-blockers and by limiting strenuous activities. In more serious cases in which weaknesses in the aorta are found, surgery can be performed.

Detection, though, is the key, and Flo Hyman deserves credit for any number of cases that have been diagnosed because her death brought about greater awareness of MFS. That started with her brother, Michael, who was found clear of Marfan syndrome but did have an enlarged aorta that required open-heart surgery.

Young basketball players are now being checked with greater frequency. Two months after declaring for the 2014 NBA draft, projected first-rounder Isaiah Austin of Baylor was diagnosed with MFS and informed by doctors that continuing to play posed too great a risk.

He did eventually receive medical clearance to resume playing and signed a series of overseas contracts beginning in November 2016, but a missed diagnosis could have been fatal.

“Flo literally was a game-changer,” Carolyn Levering, Marfan Foundation president, said in a 2014 interview. “Even today, when we have conversations with people, they talk about her.”